Home » Posts tagged 'weekly coursework'

Tag Archives: weekly coursework

Evaluating Sources Part 2: Authority & Expertise

Learning Outcomes for this Module

- LO1: Define important concepts such as: authority, peer review, bias, point of view, editorial process, purpose, audience, information privilege and more.

- LO2: Critically assess information sources in pursuit of various purposes.

- Ask thoughtful questions.

- LO4: Turn questions into strategies for retrieving a variety of information sources.

- LO6: Reflect upon your own research process.

Tools

| What You’ll Need | What We Used |

|---|---|

| Forum for discussion and reflection posts | Padlet |

| Platform to share an introduction to “Authority is Constructed & Contextual” | Microsoft365/PowerPoint & YouTube |

How to Credit Us

Except where otherwise noted, the lesson plans on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

To credit us for this module/lesson plan, cite the following:

Newman, J., Ward, S.K.L. (2025, June 11). Authority & expertise module. LIBR 100 OER. https://lib100oer.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/06/11/evaluating-sources-part-2-authority-expertise/

Authority & Expertise

Library. The Wistarion, p. 36, 1965, Archives & Special Collections, Hunter College Libraries, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York City. https://flic.kr/p/rUdf9R

Module Introduction

In this module we continue to evaluate sources. This time, we’re discussing concepts of credibility, authority, and expertise, in an academic context and beyond. At the end of the module, you will evaluate an information source taking into account concepts from this module.

This module consists of the following 4 parts:

- Slideshow presentation on authority and expertise

- Discussion post (Padlet): how authority is constructed (3 points)

- Brainstorming post (Padlet): Who is the expert or authority? (3 points)

- Discussion post (Padlet) Group evaluation of a source (4 points)

1 – Slideshow Presentation on Authority & Expertise

Watch and listen to this presentation. You can access it either on YouTube or PowerPoint online. The following discussion activity will refer back to these slides.

- Link to this presentation on YouTube

- Link to this presentation in PowerPoint (A transcript of the audio comments for each slide can be found in the “notes” section of the PowerPoint)

2 – Discussion post (Padlet): How Authority is Constructed (3 points)

In the slideshow presentation in this module we discussed the concept that “authority is constructed and contextual.” We’ve spent lots of time in this course discussing academic and news sources and how you might evaluate the credibility and authority of those sources and their authors. But the concept applies to other spaces as well. In this space, we ask you to reflect on how authority is constructed in a community that you belong to.

Crate a Padlet post in response to ONE of the following prompts:

- What is something that you consider yourself to be an expert or authority on? Who decides that you are an expert? What criteria do you and others use to determine that a person is an expert or authority on this topic? How is your expertise acknowledged and valued by others?

- Think about a community that you belong to. This could be anything: an academic group, a sports team or gaming club, a faith community, a family unit, an online community dedicated to a specific topic, a fandom, a study group, a workplace, etc. Describe how this group constructs authority. In other words, what are the formal or informal processes or criteria the community uses to decide who within the group is an authority or holds specialized knowledge?

3 – Brainstorming post (Padlet): Who is the Expert or Authority? (3 points)

When beginning research into a topic, it can be useful to think about who you consider to be an expert or authority or topic, and what aspects of the topic you think they are an authority on.

In this discussion post, you will return to the group scenarios from a past module. Check the Assigned Groups page for a reminder about which group you’re in.

Your group scenario has been posted in the column for your group on the Part 3 Padlet below. Add a post in that column discussing who you think is an authority on the topic and on what aspect of the topic (see the last slide in the video/slideshow in Part 1 above for an example). Keep in mind that there could be many different experts or authorities.

4 – Evaluating a source for authority and expertise (4 points)

In this part of the module, you and your group mates will read and evaluate an information source on the topic of your group scenario.

Your group scenario and a source on the scenario topic have been posted in the column for your group on the Part 4 Padlet below. Add a post in that column in which you evaluate that source for authority and expertise. Respond to one or more of the questions below with a substantive comment*

- What can you learn about the author(s) and/or the organization or publisher of this information? How does the information you learned relate to their authority or expertise on this topic? Do you think there are limitations to their expertise or authority?

- What can you learn about the authority or authorities cited or mentioned in the article? Do you consider them an authority or expert on the issue? Do you think there are limitations to their expertise or authority?

- Did the source include information from authorities/experts that you didn’t expect or hadn’t listed in the brainstorm Padlet above (Part 3)?

- Is the source missing the perspective of someone you consider an authority on the topic? Who else would you want to hear from? What would their perspective or expertise add to your understanding of the topic?

*Substantive comments are comments that go beyond one sentence or a simple idea. They should connect with ideas and concepts we’ve covered in class and demonstrate your process and use of different strategies. You may also connect with and build off of classmates’ comments provided you are furthering the discussion and not simply reiterating someone else’s ideas. We expect that your comments will be thorough and specific.

Information Privilege

Learning Outcomes for this Module

- LO1: Define important concepts such as: authority, peer review, bias, point of view, editorial process, purpose, audience, information privilege and more.

- LO4: Turn questions into strategies for retrieving a variety of information sources.

- LO6: Reflect upon your own research process.

Tools

| What You’ll Need | What We Used |

|---|---|

| Forum for discussion (2) | Padlet |

How to Credit Us

Except where otherwise noted, the lesson plans on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

This lesson is adapted from: Young, J. (2018). Open access: Strategies and tools for life after college. CORA (Community of Online Research Assignments). https://www.projectcora.org/assignment/open-access-strategies-and-tools-life-after-college.

To credit us for our version of the lesson, cite the following:

Newman, J., Ward, S.K.L. (2025, June 10). Information privilege module. LIBR 100 OER. https://lib100oer.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/06/10/information-privilege/

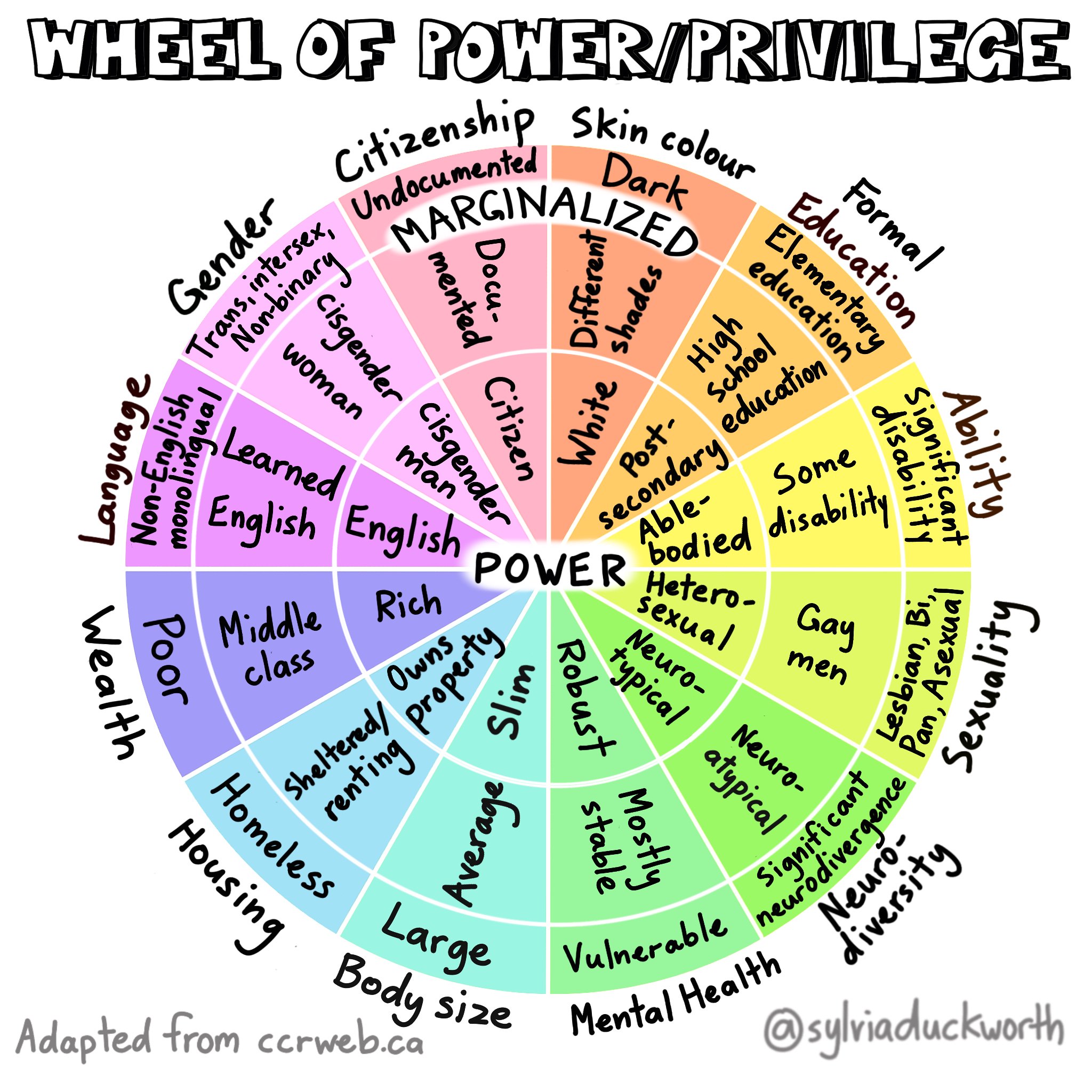

Information Privilege

Image from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sylviaduckworth/50500299716

Module Introduction

In this module we will discuss information privilege and open access (OA) resources. This module consists of the following activities:

- Read article and comment on Padlet (4 points)

- View Information Privilege/Open Access Video

- Use & write up your experience with open access tools (6 points)

Part 1: What is Information Privilege? (4 points)

- Read the Wikipedia entry on Information Privilege.

- Post on the Padlet below your response to the following 2 prompts:

- Identify an area in your life where you DO have information privilege

- Describe a time when you realized you did not have information privilege

Part 2 – Information Privilege and Open Access

Watch this video (approx. 8 minutes) on Information Privilege & Open Access. It is important to understanding the next part of the module..

Here is an updated version of the journal price survey from 2023 from Library Journal. This video was made several years ago and prices have increased.

Part 3 – Using Open Access Tools (6 points)

So what are some open access (OA) tools you can use as alternatives to paid subscription databases? There are many choices, from repositories of OA journals and books, to browser extensions that can help you locate free copies of articles. Here are a few places to look for lots more information:

- Our colleagues at the CUNY Graduate Center have this useful guide to OA resources that can get you started.

- An ever-growing list of Tools for OA, part of the Open Access Directory

- Another long list of disciplinary repositories, also part of the Open Access Directory. You can think of these as OA alternatives to our disciplinary databases (e.g. PsycINFO, Medline, AccessScience, etc.)

After completing the other parts of this module, choose two different tools or resources you learned about and use them. There are 6 to choose from on the Padlet below, but feel free to add your own in the “Your Choice” section at the bottom. Here are some suggestions, but please come up with your own ideas as well:

- Try to find an Open Access version of an article you are using for another class by using the OA button

- Search for research articles for another research project using one of the subject repositories or the DOAJ

- Use PubMed to look for research on the avian flu

- Use ERIC to find research about online/remote classroom instruction

- Choose any other tool or task that looks interesting to you – if you’re working on a project for another class this is a good opportunity to test out something new, but do not use a library database

Please don’t feel limited to the above options – you can choose how you use these tools, just remember that they are not all the same.

Lesson adapted from: Young, Jessea. “Open Access: Strategies and Tools for Life after College .” CORA (Community of Online Research Assignments), 2018. https://www.projectcora.org/assignment/open-access-strategies-and-tools-life-after-college.

Understanding URLs

Learning Outcomes for this Module

- LO1: Define important concepts such as: authority, peer review, bias, point of view, editorial process, purpose, audience, information privilege and more.

- LO2: Critically assess information sources in pursuit of various purposes.

- LO4:Turn questions into strategies for retrieving a variety of information sources.

- LO6: Reflect upon your own research process.

Tools

| What You’ll Need | What We Used |

|---|---|

| Forum for reflection posts | Padlet |

| A tool to create a self-quiz | Microsoft Forms |

| A place for students to submit/share their answers to the activity | Blog posts on our WordPress-based course site |

How to Credit Us

Except where otherwise noted, the lesson plans on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

To credit us for this module/lesson plan, cite the following:

Newman, J., Ward, S.K.L. (2025, June 09). Understanding URLs module. LIBR 100 OER. https://lib100oer.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/06/09/understanding-urls/

Understanding URLs

Module Introduction

It is easy to lose sight of the context in which information is created, especially on the internet – we all get laser-focused on finding a specific source and lose sight of how and why that source was created. In this module, you will learn to “read” and decode your the URLs of your search results in order to better understand the sources your search is returning.

NOTE: decoding URLs doesn’t apply to results you find in a library database. This strategy is only for web search results.

This module consists of the following activities:

- Internet Domains resource – how to read URLs

- Decoding URLs quiz (4 points)

- Search activity (4 points)

- Brief reflection (2 points)

Internet Domains

Read this resource from the University of Washington Libraries. Link to “Internet Domains” guide, with one correction (see below): https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/evaluate/domains

***One qualification about .org websites: the above resources states that .orgs represent nonprofit organizations. THIS IS NOT NECESSARILY TRUE. According to the Wikipedia entry for .org (emphasis is my own):

The domain name .org is a generic top-level domain (gTLD) of the Domain Name System (DNS) used on the Internet. The name is truncated from ‘organization’. It was one of the original domains established in 1985, and has been operated by the Public Interest Registry since 2003. The domain was originally “intended as the miscellaneous TLD for organizations that didn’t fit anywhere else.”[1] It is commonly used by non-profit organizations, open-source projects, and communities, but is an open domain that can be used by anyone.

You will need to understand this content before completing the rest of the activities in this module. This content applies only to Internet Domains and URLs, not to items found within research databases through the libraries.

A few things to keep in mind:

Reminder: decoding URLs doesn’t apply to results you find in a library database. This strategy is only for web search results.

A DOI, or “Digital Object Identifier” is NOT a URL. You can read more about what they are here, but please remember that they are not URLs and cannot be read or decoded the way URLs can.

A database (JSTOR, Web of Science, EBSCO, etc) is NOT a publication. A publication is the specific name of the journal, magazine, newspaper where something is published (e.g. Journal of Dance Education, The New York Times, etc).

Decoding URLs Quiz

Complete the following quiz on Decoding URLs. Be sure to enter your name so you get credit for the quiz.

*Note to instructors: we’ve included a link to the quiz template that you can duplicate using Microsoft Forms.

Search Activity and Blog Post

Choose two keywords or phrases and do a basic Google search with them.

Select two of the items in your Google results, visit the links, and write a post including the following information (you will have two sets of answers, one for each URL):

- The words you entered into the search.

- The link you investigated.

- Answers to the following questions:

- What is the domain suffix and what does it tell you about this source?

- What is the domain name and what does it tell you about this source?

- What is the title of the page you visited, and what does it tell you about this source?

Remember that you are investigating the URL and what you can learn about the source. We don’t want to know what you learned about the topic of your research, rather we want to know what you learned about the individual sources/links you investigated.

*Note to instructors: we had students post on our class website, but this could just as easily be a Padlet or other online post.

Brief Reflection

For this module you learned how to break down URLs that you find online. Write up a brief reflection about your experiences with these activities.

For your post, identify the following:

- One thing that you learned from this module that was new(ish) to you.

- One thing you still have questions about

Reading Strategies

Learning Outcomes for this Module

- LO2: Critically assess information sources in pursuit of various purposes.

- LO3: Ask thoughtful questions.

- LO6: Reflect upon your own research process.

Tools

| What You’ll Need | What We Used |

|---|---|

| Forum for discussion | Padlet |

| Tool for group annotation of an article | Hypothesis |

How to Credit Us

Except where otherwise noted, the lesson plans on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

To credit us for this module/lesson plan, cite the following:

Newman, J., Ward, S.K.L. (2025, June 9). Reading strategies module. LIBR 100 OER. https://lib100oer.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/06/09/reading-strategies/

Reading Strategies

Student sleeping in Hunter College Library, 1988. From The Wistarion, pp. 112-113, 1988, Archives & Special Collections, Hunter College Libraries, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York City. https://www.flickr.com/photos/hunter_college_archives/24719642252/

Module Introduction

One step that is often overlooked in the research process is reading the sources you’ve found to successfully understand and extract the information you need. In your college career so far, you may have already encountered difficulties reading academic/scholarly sources. These sources are generally written for experts, so it can be overwhelming to try to understand them if you don’t have the relevant background or expertise. For several reasons, reading an academic article from beginning to end the first time through may not the best strategy. In this module, we will think about strategies for making sense of scholarly journal articles. We will also think about when and how other kinds of sources might help us to understand concepts that we are not experts on.

This module consists of the following parts:

- Read “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article”

- Watch “How to Preview a Text”

- Read and take group notes on a scholarly article (asynchronous group work – 6 points)

- Read or Listen to a News Story

- Read Encyclopedia Entries Related to the Topic of the Study

- Write a reflective Padlet post (individual work – 4 points)

Part 1 – Read “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article”

Read the page “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article” from the Research Toolkit created for Hunter College by Wendy Hayden and Stephanie Margolin. (You do NOT need to do the activity at the bottom of the page)

Note that not all scholarly articles will feature all–or any–of the elements listed in the Anatomy of a Scholarly Article. Those elements are most common in the sciences and the social sciences. Articles in the arts and humanities sometimes have an abstract (though often they don’t), and they rarely have labeled sections like “Introduction,” “Conclusion,” etc.

Part 2 – Watch “How to Preview a Text”

Watch the video “How to Preview a Text” (3.5 minutes) from Excelsior University’s Online Reading Lab.

Part 3 – Take Notes Together on a Scholarly Article (6 points)

In this activity you will practice reading a scholarly article and take notes on it (asynchronously) with a group.

Please make sure you follow the instructions below in order to get full credit for this activity. You need to make at least 3 total comments (described below) on this article in order to get full credit.

- We do not want you to read the full article, but to employ some reading strategies from earlier in this module. Using some strategies you’ve read about, read/skim this article and make a minimum of 2 comments about any of the following (highlight the relevant section of text and leave your comment). IMPORTANT: Please note that if you want to comment on the same question that another student has already answered, then your comment must add something new to the conversation (not just repeat what the other person has written):

- What section(s) of the article are the most important for your understanding of the content? Why?

- What can you learn from the title of this article?

- What can you learn from the list of authors of this article?

- What did the authors set out to learn in this study? (What was their research question?)

- What did the authors do to find an answer to their research question? In other words, how did they conduct this study?

- What did the researchers learn by performing this study?

- What did the authors learn about this topic from other researchers? In other words, what past ideas and research are they building on?

- What keywords can you identify that are important to the understanding of this article? Why are they important?

- In addition to the above 2 comments, identify and make at least 1 comment on something that you don’t understand about this article.

Link to the article

Full APA citation for the article used in this activity

Smith, G. E., Chouinard, P. A., & Byosiere, S.-E. (2021). If I fits I sits: A citizen science investigation into illusory contour susceptibility in domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 240, 105338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105338.

Part 4 – Read a News Story about the Same Study

Read (or listen to) the following news story, which originally aired on the National Public Radio (NPR) show All Things Considered and has been transcribed into text. You are not required to annotate this article.

Cats Take ‘If I Fits I Sits’ Seriously, Even If The Space Is Just An Illusion

APA citation for this news story

Cats take “if I fits I sits” seriously, even If the space Is just an illusion [Radio broadcast transcript]. (2021, May 10). In All Things Considered. National Public Radio, Inc. (NPR). https://www.npr.org/transcripts/994262792

Part 5 – Read Two Encyclopedia Entries Related to the Topic of the Study

- Wikipedia entry on “Illusory Contours”

- Entry on “Visual Illusions” in the Encyclopedia of Neuroscience

(You are not required to annotate these sources)

APA citations for these encyclopedia entries

Wenderoth, P. (2009). Visual illusions. In Binder, M.D., Hirokawa, N., Windhorst, U. (eds) Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1007/978-3-540-29678-2_6356

Illusory counters. (2024, June 7). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusory_contours

Part 6 – Reflection on Reading Strategies

Please CHOOSE ONE of the following prompts and respond to it in a post on the Padlet:

- Was your strategy for reading the news story different from your strategy for reading the scholarly article? Explain how and why.

- Wikipedia is a generalized encyclopedia while the Encyclopedia of Neuroscience is what we call a specialized encyclopedia. What differences do you notice between the two? Which one was more useful to you? Who do you think the other one would be useful to?’

- We asked you to identify things you didn’t understand in the scholarly article. Describe a strategy you would use to help yourself understand one or more of these points.

- How might the different source types you read in this module (scholarly journal article, news story, entry from Wikipedia, entry from a specialized encyclopedia) be useful in different ways as you attempt to learn more about the topic?

Be sure to include your name on your post to get credit for your work.

Extra Resources (Optional)

These resources are for those who would like to learn more about reading and note-taking strategies.

Reading strategies

- “Guidelines for Critical Reading,” from the Hunter College Rockowitz Writing Center

- “‘Predatory’ Reading,” from: Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 2004). This blog post for history students discusses strategies for how to read scholarly articles in fields like history and the humanities.

- “Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources,” by Karen Rosenberg. This chapter from the open textbook Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 2 discusses strategies for reading college-level material.

- “How to Use Questioning to Improve Reading Comprehension (video),” from Excelsior University Online Reading Lab

- “Inferencing: Learn to Make Inferences While you Read (video),” from Excelsior University Online Reading Lab

Annotating texts

- “Annotating a Text,” from the Hunter College Rockowitz Writing Center

- “Annotating Texts,” from the Learning Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

- “Annotation Tips (videos),” from Excelsior University Online Reading Lab

Note-taking (in-class)

- “Effective Note-Taking in Class,” from the Learning Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

- “Successful Note-Taking: A Guide for Students,” from ACUE (The Association for College & University Educators)

Citation

Learning Outcomes for this Module

- LO1: Define important concepts such as: authority, peer review, bias, point of view, editorial process, purpose, audience, information privilege and more.

- LO5: Cite information sources accurately and discuss why we cite.

Tools

| What You’ll Need | What We Used |

|---|---|

| Forum for discussion | Padlet |

| A tool to create a self-quiz | Microsoft Forms |

| A place for students to submit/share their answers to the activity | Blog posts on our WordPress-based course site |

How to Credit Us

Except where otherwise noted, the lesson plans on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

To credit us for this module/lesson plan, cite the following:

Newman, J., Ward, S.K.L. (2025, June 9). Citation module. LIBR 100 OER. https://lib100oer.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/06/09/citation/

Citation

Xkcd. “Wikipedian Protester.” xkcd webcomic

Module Introduction

This module covers citation: what it is, why we do it, and how to check citations for completeness and correctness. We will be working with 2 of the most common citation styles, APA (American Psychological Association) style and MLA (Modern Language Association) style.

There are several other citation styles, like Chicago, AMA, and ASA, and we can’t cover them all in this course. In this module, you will practice reading MLA and APA citations and consulting citation style guides to check for errors in citations. These are skills that will be useful no matter what citation style you need to use in the future.

Please note: a link on its own is NOT a citation. Links go bad all the time; a citation gives you all the information you need to find a source, even if the link is broken.

This module consists of:

- Two brief videos

- Discussion question on Padlet (1 point)

- APA & MLA citation guides

- Citation quiz (6 points)

- Find and correct a citation blog post (2 points)

- “One thing I learned” Padlet post (1 point)

Part 1: Two Brief Videos

Please watch the following 1-2 minute videos. The first, from Clemson University Libraries, discusses the concept of the “scholarly conversation.” The second, from North Carolina State University Libraries, discusses why we cite.

“Joining the (Scholarly) Conversation” video

“Citation: A (Very) Brief Introduction” video

Part 2: Discussion Questions (1 point)

Below is a list of reasons we cite our sources. Create a Padlet post telling us which of these reason(s) you think is/are the most important and why.

- To help your reader find the sources you mention

- To place your work in the context of a larger conversation

- To give credit to others for their work and ideas

- To raise awareness of sources you think are interesting or important

- To avoid plagiarism

- To bolster the credibility of your own arguments

- To help your reader verify information or claims in your work

- To leave a trail for other researchers

- Another reason?

As always, be sure to include your name so we can give you credit.

Part 3: Review sample APA and MLA format citations

Video

Watch the following video from Santiago Canyon College which breaks down how to format a citation for a journal article according to MLA style. [This video refers to the older 8th edition of MLA, but the rules in the current edition (9th) are the same for journal article citations.]

Next, review the following citation examples from Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab, also known as Purdue OWL. Take note of what pieces of information are required in citations for different source types. You don’t need to memorize all this: you will refer back to these pages as you work on the citation quiz in this module. The Purdue OWL site is a great place to find general writing resources and guides to research and citation.

MLA format, 9th edition (full MLA citation guide)

- Articles in periodicals (“Periodicals” means anything published at regular intervals. Examples of periodicals are newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals.)

- Books (scroll down to “A Work in an Anthology, Reference, or Collection” to see how to cite a chapter from a book)

- Electronic sources, including websites, images, emails, YouTube videos, articles from periodicals that you access through online databases, etc.

APA format, 7th edition (full APA guide)

- Articles in periodicals (“Periodicals” means anything published at regular intervals. Examples of periodicals are newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals.)

- Books (scroll down to “Article or Chapter in an Edited Book” to see how to cite a chapter from a book)

- Electronic sources, including web pages, online journal articles, data sets, etc.

Notice that the general difference between citing a print source and an electronic source is that when citing an electronic source you include information about where you accessed it, including

- either a URL (check the database for a “permalink” or “stable URL”) or a DOI (Digital Object Identifier) for the source. APA style prefers a DOI over a URL when available

- the name of the database or website where you accessed the source, if applicable (This is required in MLA style only. The database used is not included in an APA style citation)

In MLA format, you are not required to list the date you accessed the online source, unless the source has no publication date or you think the source was changed or removed since the date you accessed it. Similarly, in APA format you are only required to include a date of access for sources that may change over time, like a website or a wiki, but not for an ebook or journal article, because those generally do not change once published.

Part 4: Citation Quiz (6 points)

This quiz consists of 20 multiple choice and short answer questions.

You will be asked to identify source types, to identify various components of APA and MLA citations, and to identify errors in APA and MLA citations.

The learning objectives of this exercise are as follows:

- read and understand APA and MLA citations

- compare citations to APA and MLA style guidelines, checking for completeness and correctness

Refer back to the resources in Module 2.3 if you need help.

Once you have answered all the questions, you may click “view results” to see the correct responses to the multiple-choice questions.

You will earn 6 points for completing this quiz.

Part 5: Find and correct a citation (2 points)

Using OneSearch, the main search box on the Hunter College Libraries website, search for any topic you want. Choose one source from your set of search results and use the “citation” tool in OneSearch to generate a citation in either APA or MLA format. You may choose any type of source (book, news article, journal article, etc.)

Create a blog post on our site that includes the following:

- Which style you chose: APA or MLA

- What type of source you chose

- Copy/paste the OneSearch-generated citation without making any changes

- Identify what is wrong with or missing from the citation (if anything)

- Your corrected version of the citation

Part 6 “One Thing I Learned” Padlet Post (1 point)

Create a brief post describing one thing you learned in this module about citation, and one thing that you still have questions about.

Internet Search Engines

Internet Search Engines

In this module we will be learning more about internet search engines, including everyone’s favorite, Google. Although Google dominates the internet search world, and it can be an excellent tool to use, it is not the only search engine out there. We ask you to look more closely at some of the problems with Google, and explore some alternatives to Google as your only search engine.

This module contains the following:

- “What Google Search Isn’t Showing You” (reading)

- “Just Google It” (video)

- Search Engines Worksheet (8 points)

- Reflective Blog Post (2 points)

What Google Search Isn’t Showing You

Read the following brief article from The New Yorker magazine: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/what-google-search-isnt-showing-you

Full MLA citation for the article:

Chayka, Kyle. “What Google Search Isn’t Showing You.” The New Yorker, 10 Mar. 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/what-google-search-isnt-showing-you. Accessed 25 Mar. 2022.

Just Google It

Watch this brief clip (~4 minutes) from Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble’s talk. Her book, Algorithms of Oppression is available as an e-book from the New York Public Library if you’re interested to read more (or you can watch the rest of her talk on YouTube).

The video will keep playing, but you can stop watching at 19:26 after her comments about the academic vs. advertising perspective on Google.

Search Engines Activity (8 points)

Create your own copy of the following worksheet on your device, on Microsoft Office 365 online, or anywhere you save your documents. Type you answers directly into the document.

Brief Reflection (2 points)

Write a brief reflection post responding to the following prompt:

Reflect back on the reading, the video, and the search engine activity. Describe anything from this module that surprised you or introduced something new to your approach to internet searching. What is one thing that frustrated you about the work for this module, or that you did not find useful? What is one new thing you will try moving forward?

*Note to instructors: we had students create a post on our website, but this could easily translate to other formats such as Padlet, Jamboard, etc.

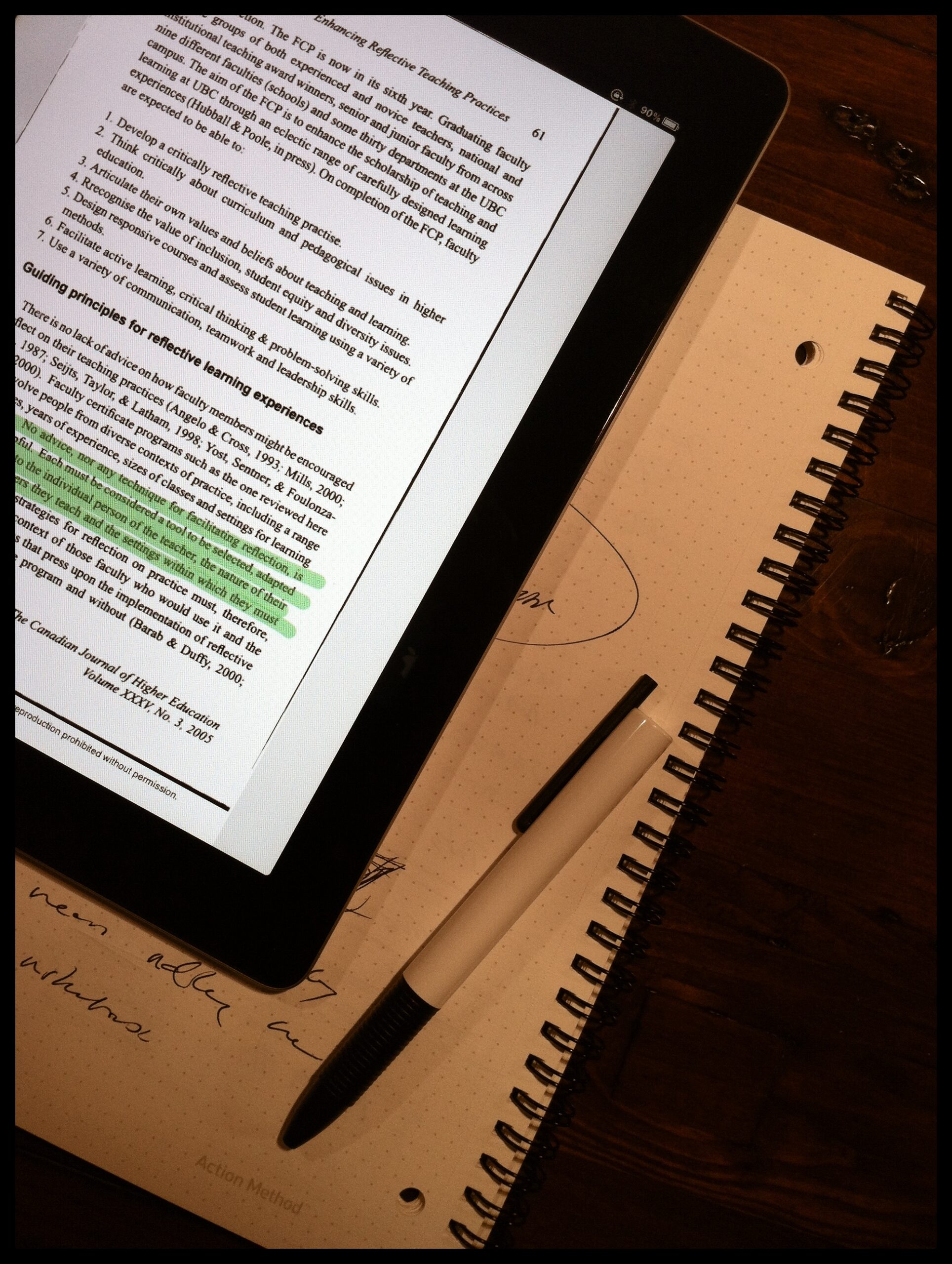

Reading Strategies (2022 version)

Reading Strategies

teachandlearn. “On My Desk 2012: Day 17.” Photograph. Taken on January 17, 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/teachandlearn/6717612245/. Creative Commons license information.

One step that is often overlooked in the research process is reading the sources you’ve found. In your college career so far, you may have already encountered difficulties reading academic/scholarly sources. As we’ve discussed, they are generally written for experts, so it can be overwhelming to try to understand them if you don’t have the relevant background or expertise. For several reasons, reading an academic article from beginning to end the first time through may not the best strategy. In this module, we will think about strategies for making sense of scholarly journal articles.

This module consists of the following parts:

- Read the article “Reading Games: Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources”

- Read and view the tutorial “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article” and complete the associated “Reading Scholarly Articles” activity

- Take group notes on a scholarly article (asynchronous group work – 6 points)

- Write a reflective Padlet post (individual work – 4 points)

Part 1 – Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

Read the page “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article” from the Research Toolkit created for Hunter College by Wendy Hayden and Stephanie Margolin.

AND

Complete the “Reading Scholarly Articles” activity from the same Research Toolkit.

Note that not all scholarly articles will feature all–or any–of the elements listed in “Anatomy of a Scholarly Article.” Those elements are most common in the sciences and the social sciences. Articles in the arts and humanities sometimes have an abstract (though often they don’t), and they rarely have labeled sections like “Introduction,” “Conclusion,” etc.

Part 2 – Strategies for Reading Scholarly Sources

Please read this post on “Predatory” Reading from Bowdoin University history professor Patrick Rael. This comes from a website made for history students, but this advice is useful for scholarly sources in many fields. Take note of things that might be useful to you when you are reading for research. You should read this first before proceeding to the rest of the activities.

From: Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 2004). https://courses.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

Note to instructors:

In the past, we’ve assigned the following OER chapter instead of the post on predatory reading:

Rosenberg, K. (2011). Reading games: Strategies for reading scholarly sources. In C. Lowe and P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings on writing (Vol. 2, pp. 210-220). Parlor Press. https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=176.

Part 3 – Take Notes Together on a Scholarly Article (6 points)

This is a group reading strategies activity. However, you can complete this work on your own time, asynchronously, even though you will be commenting on the same document as your group members. Please make sure you follow the instructions below in order to get full credit for this activity. You need to make a minimum of 3 comments (described below) on this article in order to get full credit.

- Open up the link to the assigned article. We do not want you to read the full article, but to employ some reading strategies from the earlier parts of this module.

- Using some strategies you’ve read about, read/skim this article and make a minimum of 2 comments about any of the following (highlight the relevant section of text and leave your comment):

- What sections of the article are the most important for your understanding of the content? Why?

- What can you learn from the title of this article?

- What can you learn from the list of authors of this article?

- What is the main idea or argument of this article?

- What keywords can you identify that are important to the understanding of this article?

- In addition to the above 2 comments, identify and make at least 1 comment on something that you don’t understand about this article.

How to annotate this article using Hypothesis

- Click on the appropriate link below to join the Hypothesis group that corresponds to your group number for this course

- Log in to your Hypothesis account (which you created back in the week 1 Orientation Module)

- Return to this page and follow the link below to open the article. You should see the Hypothesis menu on the right side of the screen

- Make sure to switch your Hypothesis settings from “public” comments to comments in your group (example: “LIBR100Fa22Group1”)

- Highlight relevant text in the article and leave your comments

Group links

[group links here]

Link to the article

[link to assigned article here]

Note to instructors:

We use hypothesis for social annotation in this course. Hypothesis works only on publicly available websites, so this activity doesn’t work for articles behind a paywall. You can use hypothesis for this activity with an open access journal article of your choice.

Part 4 – Reflection on Reading Strategies (4 points)

Please post a 1-2 paragraph response to the following prompt on the Padlet:

We asked you to identify some things you didn’t understand in the article for this module. Describe a strategy you would use to help yourself understand one or more of these points. Reminder: we’ve covered a lot of tools and strategies so far in this course. Think about those, as well as your own past research experience, and draw on all those things to describe your strategy.

Be sure to include your name on your post to get credit for your work. Post on the embedded Padlet below or access the Padlet here.

Note to instructors: Padlet is a proprietary tool that we use through an institutional subscription. You can make a free account which allows you to make a limited number of Padlet boards at one time. You could also adapt this activity to be used with the message board or blog post system in your institution’s Learning Management System, or with another digital tool like Google’s Jamboard.

Acknowledgements

This module refers students to portions of the following resources:

- Wendy Hayden & Stephanie Margolin, Research Toolkit, Hunter College.

- Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 2004). https://courses.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

A previous iteration of this module used a chapter from the OER textbook Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing.

Asking Questions

Asking Questions

Question Mark Sign On Hobson’s Old Building, Corner Of Henry & Main (Honor, MI). By flickr user takomabibelot, Public Domain, https://www.flickr.com/photos/takomabibelot/472933624/

Questions are the foundation of all research – questions show curiosity and an interest in learning more. Asking questions is a natural part of human development, and something we all do as children without even thinking about it. As we get older, our ability to ask many and varied questions seems to taper off. For this class, and for this lesson, we’d like you to get back in touch with that question-asking ability.

Simple questions can be incredibly powerful. Complex questions can be broken down into smaller, more manageable questions. Silly questions can lead to a serious line of inquiry. There are no “stupid” or “wrong” questions here – just the opportunity to be open and curious, and to discuss your curiosities with your classmates. The only bad question is one that you don’t ask. This module consists of 2 activities:

- Individual question brainstorming and identifying Open- and Closed-ended questions (4 points)

- Group work with questions & scenarios (6 points)

Part 1 – Asking Questions (4 points)

This is an individual activity that has two parts. Select either an encyclopedia entry or a news source about your topic as a starting point for this module.

*Note to instructors: you can also pre-select a source for the students to use as a starting point. A variety of sources could work well for this. We have used images, news articles, excerpts from academic articles, and encyclopedia entries.

Group topics are:

- Housing & New York City

- Public Health & Pandemics

- Abortion & Reproductive Rights

- Censorship & Schools

- Climate Change & Extreme Weather

- Gun Policy & School Shootings

- Diversity & Representation in the Entertainment Industry

Read the source you’ve chosen. You’re going to ask questions based on what you read in that source, with your topic in mind as a focus. There are some rules for asking questions we want you to follow:

- Rule 1 – Ask as many questions as you can

- Rule 2 – Do not stop to judge or try to answer your questions

Follow these steps for the activity:

Part 1.1 – Asking Questions Activity:

- Read your chosen source – you should use one you found in Module 4.

- Get out a blank piece of paper or open a blank document on your device.

- Set a timer for 5 minutes.

- During that 5 minutes, write down as many questions as you can think of about your topic, following the two rules above. Try to ask questions for the full 5 minutes.

You will be using these questions for the rest of this module as well, so hang on to them!

Part 1.2 – Identifying Open and Closed-Ended Questions

Different types of questions can be used for different purposes in research and in life. Questions are often categorized as open-ended or closed-ended questions.

A former student offered this explanation of the main difference between open- and closed-ended questions:

Closed-ended questions are for when you want an answer. Open-ended questions are for when you want to start a conversation. – Dezwon, LIBR 100 student, Spring 2020

Sometimes we need an answer; sometimes we need to explore and engage in conversation. Some questions don’t fit into either category and instead fall somewhere in between. A few things to look for:

- Closed-ended questions often have a single answer, or they can be answered with a single source of information

- Open-ended questions often require a complex or nuanced answer, or may require engaging with multiple sources of information

Activity:

- Identify one open-ended question and one closed-ended question by labeling/highlighting/circling them on your question list from above.

- Post an image of your question list to the Padlet below (be sure to include your name!)

Part 2 – Questions and Scenarios (6 points)

Work with your group to complete this assignment. Submissions will be on a group Padlet (linked below).

Please post the following on your group’s Padlet for this assignment:

- Choose 3 questions from your individual list to share with your group, and post them on the Padlet.

- Label each question as open or closed – note if there are questions that don’t fit neatly into one or the other category, and please comment on each other’s posts until you can reach some sort of agreement

- Look at your group’s scenario (posted below) and together, decide which of your group’s questions would be appropriate to the task set forth in the scenario, or any new questions you agree on that will help you for the scenario – choose 2-4 questions

- Together, start a list of the kinds of information sources you might need in order to address the scenario. We are looking for something more specific than “books” or “articles.” Use the knowledge you have, to create your list of information sources that will help you understand, explore, and/or address this scenario.

Scenarios

*Note to instructors: these are scenarios we created in Fall 2022. We update them periodically to bring in current events.

Housing & New York City

You are trying to help out some family members, whose building has just been sold, find out what their rights are as tenants in a New York City rent-stabilized apartment.

Public Health & Pandemics

You are trying to sort out, for yourself and your loved ones, the truth from misinformation being reported about various current public health concerns in New York.

Climate Change & Extreme Weather

You work for an organization that advises local waterfront communities about preparedness for extreme weather events, and you have to give a presentation at an upcoming community meeting.

Gun Policy & School Shootings

You work for a local politician who wants to influence policy about guns/firearms, and they have asked you to research school shootings in your state.

Censorship & schools

You are a parent with a school-aged child and you’ve been hearing a lot about censorship issues related to school curriculum and reading materials. You want to educate yourself about what is happening so you can speak to your school’s PTA at the next meeting.

Diversity & representation in the entertainment industry

You work as a research assistant for a journalist who is writing a book about diversity & representation in film and television. They have asked you to gather information about the conversations happening around this issue as it relates to people both on-screen and behind the scenes.

Abortion & reproductive rights

You are a voter who is concerned about sudden changes in abortion laws in various states in the US, but you don’t feel you have a complete understanding of the medical details of abortion or the history of abortion laws.

*Note to instructors: we made a Padlet of Padlets for this module in order to streamline the process for students. You can view the template here. We populated it with a Padlet for each group (template linked below) that included the prompts for the activity.

This lesson was adapted from the following:

- Brown, Mason; Margolin, Stephanie; and Ward, Sarah Laleman, “SEEK Summer Bridge Program in the Hunter College (CUNY) Libraries 2018” (2018). CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_oers/7

- Rothstein, D. & Santana, L. (2011). Make just one change: Teach students to ask their own questions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Background and Preliminary Research

Background and Preliminary Research

For this Module, we are going to start locating resources for beginning your research. These resources can apply for both school-related research and life-related research. Please complete the following:

- Background and Preliminary Research slide show (lecture/video)

- Claim your free online newspaper accounts (activity)

- Find your sources (individual post on website, 5 points)

- Evaluate a source (group post on Padlet, 5 points)

Part 1 – Background and Preliminary Research Lecture

Please watch/listen to this slide show for the contents of today’s lesson. There are audio comments on each slide, which you can listen to by clicking the audio icon in the upper left corner of the slide.

To play the slides, click “present” in the upper right corner, and the audio should start automatically. I’ve also included my audio comments in the “speaker notes” section on each slide if you prefer to read them

Included in the slides are two brief screencasts about using OneSearch* to find your sources. Please be sure to watch these!

*Note to instructors: OneSearch is Hunter’s primary search tool on our library website. The screencasts are specific to this, but we found it necessary to show students exactly what we expected them to do.

Part 2 – Claim your free newspaper accounts!

*Note to instructors: these are the two institutional, direct-access newspaper subscriptions we offer to students. Feel free to change this or eliminate this part of the exercise.

CUNY students can claim two free online subscriptions with a valid CUNY email address: The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. By claiming your accounts, you gain access to both of these major newspapers directly though their websites without having to go through the Hunter Libraries site. No more paywalls for you while you’re a student!

New York Times Academic Pass: NYTimes.com/passes

Wall Street Journal: www.wsj.com/Hunter

Part 3 – Find Your Sources (Individual, 5 points)

Review the screencasts in the slideshow at the start of this module for information about using OneSearch for Reference Entries and for Newspaper Articles. Use your assigned group topic for your search. Please select TWO specialized reference entries and ONE news article related to your topic.

Group topics are:

- Housing & New York City

- Public Health & Pandemics

- Abortion & Reproductive Rights

- Censorship & Schools

- Climate Change & Extreme Weather

- Gun Policy & School Shootings

- Diversity & Representation in the Entertainment Industry

Create a post on our site in response to the following:

- Write an APA-style citation for each of your sources – see samples below. (You will have 3 citations: 2 specialized reference entries and 1 news article. If you use the citation generator in OneSearch please make sure your citation is complete – there should be enough information for someone else to find your source again, including a permanent link).

- What words did you enter into the search box? Please be specific and include all the words you used in your search, exactly as you entered them.

- What OneSearch filters did you use?

- What other filters or sorting options did you use (if any)?

- What is one thing you learned doing this activity, or one thing that remains unclear to you?

APA style samples

Your citation must include all the information needed to find the source again. Use the APA style site for reference: https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/references/examples

AuthorLastName, AuthorFirstInitial. (date, or n.d. if no date is available). Entry or article title. Title of the publication. permanent link (if available)

News article:

Carey, B. (2019, March 22). Can we get better at forgetting? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/22/health/memory-forgetting-psychology.html

Reference entry:

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Just-world hypothesis. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved January 18, 2020, from https://dictionary.apa.org/just-world-hypothesis

Part 4 – Evaluate a source (group, 5 points)

We chose* either a Reference or News source for each group, related to the topic you were given, and posted the citation to the group Padlet. Evaluate the source and write up what you learned by posting the following in your group’s column on the Padlet below:

- Put your name on your post!

- Process: What did you learn about how this source was published? What is the process by which this information was created and published?

- Authority/Expertise: Who is the author of the source? What can you learn about the author? Do they have relevant expertise to write about this topic? What gives them authority to write about the topic?

- Aim/Purpose: What is the purpose of this piece of information? What does the author (or publisher) want you to do as a result of reading this information? Is it informational, persuasive, a call-to-action, etc?

- Challenges: Identify any challenges you/your group encountered in completing this activity.

*Note to instructors: we choose sources based on the assigned topics and try to keep them as current as possible.

Introduction to Evaluating Sources

Introduction to Evaluating Sources

Bateman, Dayna. “Research.” Photograph. Uploaded on November 25, 2006. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/suttonhoo22/305806118/. Creative Commons licensing info.

In this module we’ll be thinking about how to evaluate the sources we find. The first step in evaluating a source is to identify what type of source it is, which can often help you to decide whether the source matches your information need. In this module, we’ll be working with some types of sources that you might find in a library database, such as newspaper articles, encyclopedia articles, journal articles, and e-books.

Here is the outline for this module. All parts of this module are due on [due date].

- Identifying Source Types Mini Quiz (2 points)

- Evaluating Source Types Padlet Post (1 point)

- Matching Sources to Scenarios Group Padlet Posts (3 points)

- Reflection on Source Types Blog Post (4 points)

Part 1 – Identifying Source Types Mini Quiz (2 points)

The first activity in this module asks you to identify types of sources based on their citations in MLA format. You may want to do these optional activities first.

Optional activities: Guides to MLA citation

If you’re not familiar with MLA citation style, or if you need a refresher, we recommend the following video from from Santiago Canyon College which breaks down how to format a citation for a journal article according to MLA style. [This video refers to the older 8th edition of MLA, but the rules in the current edition (9th) are the same for journal article citations.]

We also recommend looking at the following citation examples from Valencia College Library. We find their color-coded guide very useful and clear!

- MLA format, 9th edition

Click here for Valencia College Library’s full MLA citation guide

Required activity: mini-quiz

For 2 points, fill out the mini quiz in the embedded form below, or access the mini quiz at this link. Take note of the correct answers (=which citation corresponds to which source type). You will need that information for the next activities in this module.

If you would like to work out your answers on a worksheet before submitting the mini-quiz, you can download a copy of a worksheet below (this is optional and you will not submit this worksheet to us).

Note to instructors: You can copy our Microsoft Form template for this activity.

Part 2 – Evaluating Source Types Padlet Post (1 points)

After identifying each source type in activity 3.1, click on the links below to open and skim each source (you do not need to read them in full for this exercise). All of these sources cover the topic of caffeine, but in different ways. Think about what characteristics make each source type distinct. Below we list the citations and links to the sources and a list of aspects to consider.

Tech note: Most of these sources are behind a paywall and are available through the Hunter College Libraries. To access them, you will need to log in with your Hunter NetID.

Citations List

[Make sure you’ve correctly identified which citation corresponds to each source type. Refer back to your answers and corrections from the mini quiz in 3.1]

1) Brody, Jane E. “Scientists See Dangers in Energy Drinks.” The New York Times, 1 Feb. 2011, p. D7. Nexis Uni, https://advance-lexis-com.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:522Y-F9F1-JBG3-62BT-00000-00&context=1516831.

2) “Caffeine.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Jul. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/science/caffeine.

3) Mednick, Sara C., et al. “Comparing the Benefits of Caffeine, Naps and Placebo on Verbal, Motor and Perceptual Memory.” Behavioural Brain Research, vol. 193, no. 1, 2008, pp. 79–86. Science Direct, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2008.04.028.

4) Preedy, Victor R, editor. Caffeine: Chemistry, Analysis, Function and Effects. Royal Society of Chemistry, 2012. https://pubs-rsc-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/en/content/ebook/978-1-84973-367-0.

5) Rippe, James M. “Caffeine.” Encyclopedia of Lifestyle Medicine & Health, edited by James M. Rippe, vol. 1, SAGE Reference, 2012, pp. 169-171. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX1959000064/GVRL?u=cuny_hunter&sid=GVRL&xid=e00cae1a.

6) Urwin, Rosamund. “Count Me Out of This Caffeine-Addled Nightmare.” London Evening Standard [London, England], 12 July 2010, p. 15. General OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A231329356/ITOF?u=cuny_hunter&sid=ITOF&xid=7b1d23cb.

Criteria to think about

- Authorship: Who writes this kind of source?

- Audience: Is this written for the general public? For students? For professionals in a given field? Someone else?

- Scope: Does the source cover the topic broadly or does it narrow the focus to 1 or 2 specific aspects?

- Depth: Does the source go into detail about the topic, or does it only give an overview?

- Originality: Does the source include original findings by the author/s, or does it report on the findings of others? Or both?

- Novelty: Does the source report new information or information that has already been established?

- Language & Tone: Formal or informal? Impersonal or personal? Plain & simple language or jargon? Is the text understandable to a non-expert?

- Purpose: Was this written to educate? To share new information or a new argument? To entertain? To persuade? To make a political argument? As cultural commentary? Something else?

Full-class Padlet exercise – make 1 post

On the Padlet below, make 1 post, following these instructions:

- Post underneath a source type listing one characteristic of that source type (refer back to the criteria listed above for ideas). For example, under newspaper article (report), I might post “Newspaper articles are written for a general audience.”

- Discuss only one characteristic in each post. (For example, do not post “Newspaper articles are written for a general audience and usually present new information” in a single comment)

- Do not repeat something already listed in another post, unless you are disagreeing with or modifying what’s written in that post

Once everyone in class has contributed to the Padlet, we should have a full grid summing up the ways in which each source type might cover the same topic in different ways. As a researcher or information seeker, this is something that will factor into your decision when choosing an appropriate source for your information need.

Note to instructors: If you have a Padlet account, you can recreate this Padlet, and all the others we’ve made.

Part 3 – Matching Sources to Scenarios Group Padlet Posts (3 points)

Now that you’ve thought about how different source types might cover a topic in different ways, it’s time to match these sources to an imagined scenario or task. This activity will be done in your assigned groups.

Next, open your group’s Padlet in a new window and make 3 posts, following this instructions:

- Create a post under a scenario listing which source from this module you’d use in that scenario

- Each post should list both the title of the source and the type of source it is. (For example, “In this scenario, I would use the newspaper article ‘Scientists See Dangers in Energy Drinks’ because…”)

- Each post should say why you think that that source is the most appropriate one for the task

- Make sure to take into account not only which kind of source is useful in each scenario, but also whether this particular source is a match for the scenario. Would the information in that source really help answer your question in that scenario?

Note to instructors: If you have a Padlet account, you can recreate this Padlet, and all the others we’ve made.

Recent Comments